Long-COVID sufferers are conserving strength with a "hack" of their fitness tech

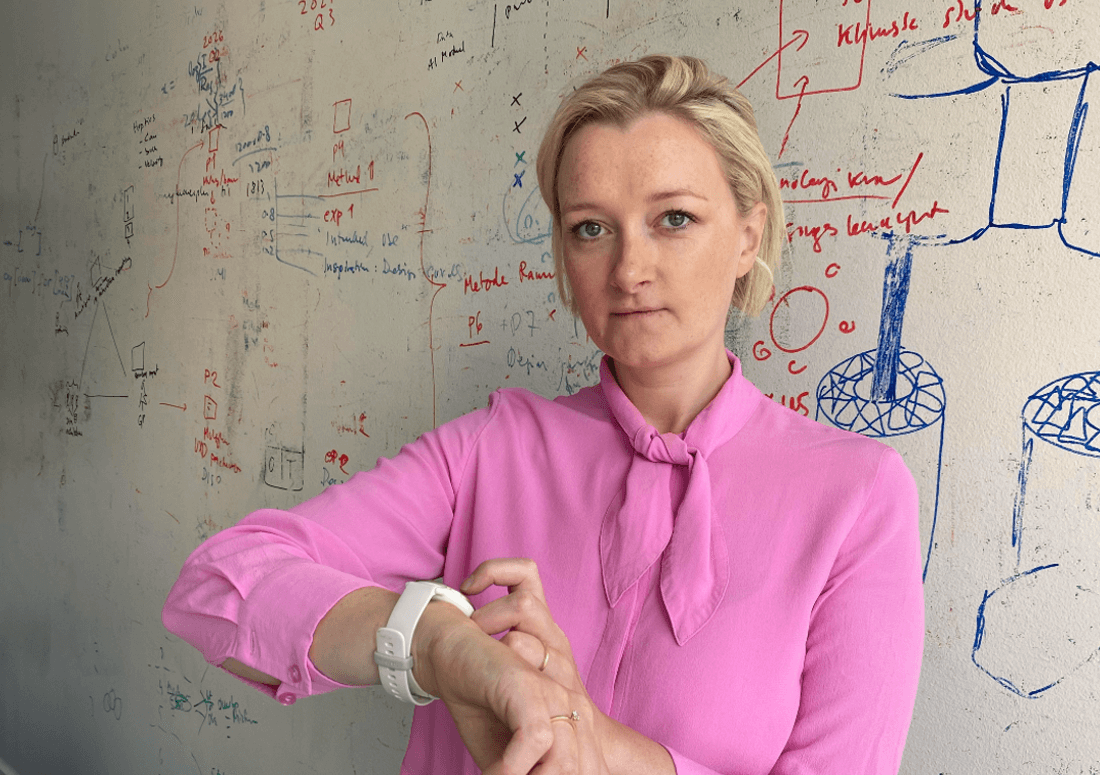

When people suffering from the long-term effects of COVID-19 faced more questions than answers from doctors, they began collecting data on themselves using fitness watches to better understand their disease. University of Copenhagen researcher Sarah Homewood was one of them and has since researched the phenomenon. According to her research, while self-monitoring can offer people more certainty and control over the disease and their bodies, it can also lead to anxiety.

"Time to get up", "You've walked less than average", "You can still reach your activity goal"... An ever-growing number of people are being paced forward over the past few years by small wearable technology – typically worn around the wrist like a watch, with built-in sensors to monitor their physical activities and health.

Whether as sports watches, fitness trackers or software enabled smartwatches, these devices are now being used to manage disease as well, serving beyond their intended purpose as fitness-tracking technology.

Long COVID is an example of a disease where sufferers have used fitness tracking watches, contradictory to their intention and design, to limit strenuous activities and conserve energy. E.g. by making sure their heartrate didn’t go to high on walks or deciding whether or not to shop for groceries based on the steps already tracked.

Sarah Homewood, an assistant professor at the Department of Computer Science, has experimented with this on both her own body and through research. She is behind two studies, both of which examine the use of fitness technology for long COVID-related self-monitoring.

In her most recent article, she examines the use of fitness trackers among twenty-one individuals with long COVID and concludes that self-monitoring has both good and bad aspects for users:

"Across all participants, the most common traits were a sense of greater control and certainty about the disease, better opportunities to document symptoms to oneself, family and their doctors, but also situations of uneasiness or anxiety triggered by use," says Sarah Homewood.

The researcher highlights one participant's visit to a float tank as an example. The visits had been a peak of relaxation for the woman, until data from her fitness tracker reported elevated stress levels, after which the woman stopped going to the activity.

"There is a clear tendency for data to eclipse experience. The data users get can have a major impact on how they assess situations. In some contexts, it can be a source of unrest, while in others, certainty and security," says the researcher.

Not used as intended

The results also support her first research study on the subject – a so-called autoethnographic study of her own illness and use of self-monitoring. The researcher’s experiences as a long-COVID sufferer using of a Fitbit watch didn’t just evolve into her research study, they served as her personal path to recovery.

"I quickly realized that I needed to use the watch contrary to its intentions. I had to counter its design. Whenever the watch informed me that I had walked far and needed to keep going to reach a new distance goal, it was my cue to sit down. Because the watch provided me with 'hard evidence' to compare my experiences with, I could actually begin to piece together what worked and what exacerbated problems for me," says the researcher.

Sarah Homewood was able to adjust her physical activities based on the watch's heart rate readings, and in doing so, avoid paying a hefty price for overexerting herself. Ever since, she has seen this "hack" of the watch's functionality to control her own physical activities mirrored in the new study’s participants.

More info: Her own experience

Sarah Homewood was struck by COVID-19 in the fall of 2020. She experienced mild symptoms at first, but the disease dragged on and eventually worsened. She was affected by what we know today as long-term or long COVID.

"I couldn't catch my breath, was constantly tired and couldn’t concentrate. It took a long time for me to understand what I was experiencing, as the long-term effects were an unknown phenomenon at the time," says Homewood, a researcher at the Department of Computer Science.

Homewood found the long-term disease difficult to deal with, partly due to the skepticism of the health professionals she interacted with. Knowledge about the disease was very limited at the time. Oftentimes, her symptoms were explained away or outright dismissed.

"I came in with slightly diffuse symptoms, primarily enormous fatigue. And even when not stated directly, it was in the air that these symptoms were probably psychological or exaggerated. Even though the disease progressed to the point where I could barely walk or speak, and my heart rate became extremely high at the slightest exertion, it contributed to me beginning to doubt my own experience," she explains.

Seeking clarification, Homewood purchased a Fitbit watch, which she says marked a turning point.

Triggered anxiety attacks after a walk

Today, the effects of long Covid are a recognized disorder with a complex pattern of symptoms that medical science continues to try to unravel. For starters, the common mindset that all exercise and physical activity is healthy is no longer the consensus. Today, the term “post-exertional malais” is used to describe the negative consequences that people with long COVID can experience after even minor efforts. This is a price that can often extend for days.

"The watch became a tool for me, where I could see in raw data when my limits had been reached. Still, I was occasionally knocked off course because the watch wanted something quite different out of me. A year later, while recovering and on a trip with some friends, the watch triggered an anxiety attack when it suddenly informed me that I had broken a record for the number of steps in a day. I was afraid that the exertion would backfire and make me sick again," she says.

"That incident made me think more about the negative aspects of using this type of tool. While the watch was simply reporting what had already happened, access to that raw data can be overwhelming. It inspired me to investigate the use of these devices among other people with long COVID – both the good and the bad," says Sarah Homewood.

The new study confirms

The new study shows that both the positive and negative aspects experienced by the researcher are recurrent trends.

Participants find that wearable fitness technology gives them more certainty that their experiences are real, and that they gain a degree of control over the disease and their body by using the data to understand and regulate their energy expenditure, among other things. The reality for the participants where an unknown disease without a name. The measurements therefore become a way to understand a new disease that, despite resistance, can then be presented to a doctor for documentation.

The study shows that some of the participants’ doctors flatly rejected watch data. Other participants were met more positively, and some were even able to use it directly and get a diagnosis from the doctor.

"This is something relatively new and healthcare professionals need to get used to the fact that this type of data exists when they meet patients. But since fitness watches aren’t approved or designed to be medical devices, the information should also be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, I don't think it's appropriate for doctors to be totally dismissive," says the researcher, and continues:

Where a number of doctors may be skeptical about the idea of self-monitoring because they fear that it can lead to anxiety in laypeople and unnecessary doctor visits, Homewood points out that the opposite is also often the case: many participants express a feeling of empowerment in being able to do something to help themselves.

She also emphasizes that technology can really help.

"Take my example: despite nearly fainting, measurements taken at the doctor showed nothing. Data from the watch revealed that it was due to my heart. For this, I am grateful. But of course, we need to help this technology along and develop it with respect for its possibilities and as well as the risks that exist in the form of unnecessary anxiety, erroneous self-diagnosis, etc.," says the researcher.

Pointing out that even though data from these watches are yet imprecise, the watches are able to collect data from longer periods, which gives the ability to see trends, rather than just the one data point measured in the doctor’s office.

“Also this technology will improve. It is here to stay. We need doctors who embrace the technology and relate to the opportunities and risks that exist, and in doing so, help it to develop," she says.

Better software on the horizon

The researcher currently in contact with several companies that are working on software improvements tailored for diseases.

"It isn’t ideal for people who are ill to be measured by apps intended for sports and fitness. Being compared to a healthy body and asked to do more, when one’s own body doesn’t want to, can be an unpleasant experience. It gives feedback to people who are ill that isn’t appropriate and can trigger anxiety," she says.

The researcher is also trying to speed up the development of a dashboard interface for presenting data that bridges the gap between self-monitoring patients and their medical providers.

"There is a need to improve communication between those who use these tools and their doctors about their data. That's why we're working to develop a dashboard that can be used differently by users and healthcare professionals. In doing so, users will gain a better overview, while doctors can access details that require a trained eye to interpret," says Sarah Homewood.

Facts: About the study

While people often consider COVID-19 a thing of the past, many continue to suffer from the long-term effects of the disease. Between April 2023 and January 2024, Sarah Homewood conducted a study of 21 participants recruited from social media groups related to COVID-19.

6 men, 13 women and one non-binary person with an age range from late twenties to mid-sixties participated, reflecting the skewed disease distribution regarding both gender and age, and the users of self-tacking technology in society.

Homewood’s research team conducted semi-structured interviews with the participants, all of whom suffered from the long-term effects of COVID-19, and on their own, like herself, had used wearable fitness technology to monitor their disease.

The limited energy of participants was one challenge confronted by the researchers. Adapted methods, breaks and online interviews ensured that the research did not negatively impact participant health.

Contact

Sarah Homewood

Assistant Professor

Department of Computer Science

University of Copenhagen

sfh@di.ku.dk

Kristian Bjørn-Hansen

Journalist and Press Contact

Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

kbh@science.ku.dk

93 51 60 02