Foundation and the first years

Need for a Department of Computer Science

In 1966, the same year in which Peter Naur invented the term ‘datalogy’, the University of Copenhagen set up a computing committee entrusted with examining the University’s need for electronic data processing. The committee decided that the University of Copenhagen was to have a joint data processing centre that all study programmes at the University could use. In addition, computer science was to be taught at all faculties, and an actual computer science line was to be set up for mathematics students wanting to specialise in computer science.

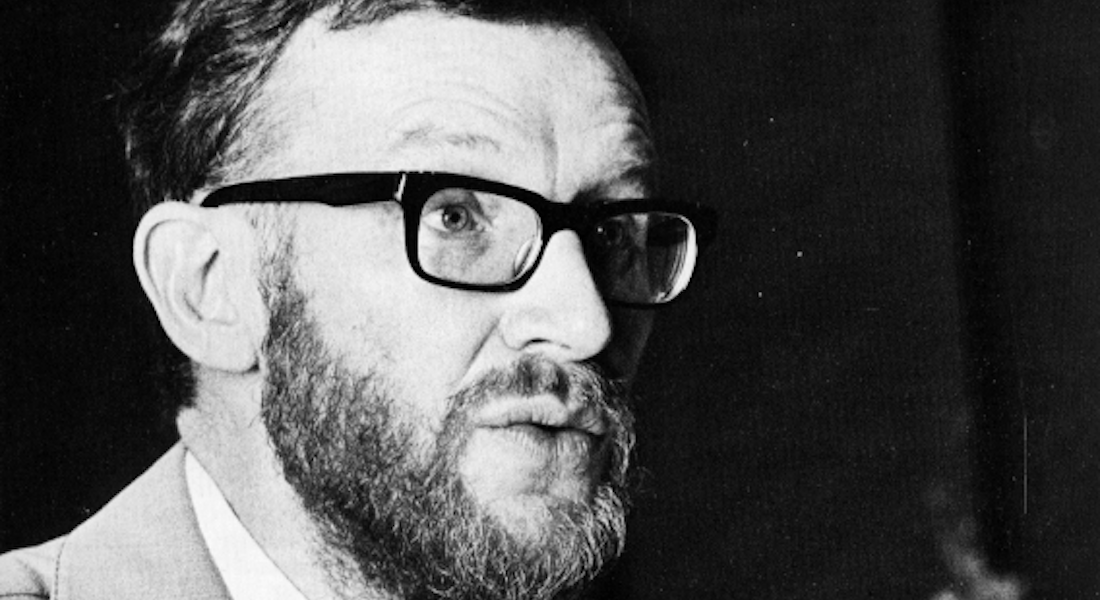

However, a new and extended plan was presented in 1968. A professorship in computer science was to be established as soon as possible, and immediately after the professorship had been filled, a department of computer science was to set up which would be responsible for the future development of the discipline. The professorship was filled with Peter Naur in 1969, and the Department of Computer Science at the University of Copenhagen – DIKU – was founded in 1970. A tiny new department located in the basement of Building E under the Hans Christian Ørsted Building on Nørrebro in Copenhagen had now been born.

When the Department was founded in 1970, it had 40 employees. The academic staff members consisted of a professor, three fixed-term lecturers (a temporary teaching position for graduates), two full-time associate professors, four part-time associate professors, and 24 instructors. The administration consisted of two secretaries and four technical assistants. The programme was popular from the outset, and the Department taught more than 500 students.

Computer science for all

To begin with, DIKU was given a faculty-independent administrative position – a visionary move that showed awareness of the importance of computer science to all disciplines. Computer science has thus traditionally had an interdisciplinary spirit, with computer scientists wanting to collaborate on an equal footing with all disciplines.

Computer science skills were never reserved for mathematicians – on the contrary. Many computer science students combined their studies of computer science with the humanities, social sciences, or business-oriented subject areas. However, in 1976, DIKU was placed under the Faculty of Science and was based in Sigurdsgade in Nørrebro.

Student co-determination and practice-oriented teaching

The first years of DIKU were especially spent on building up an understanding of what computer science was to contain as a discipline and how DIKU should be organised. From the outset, Peter Naur attached importance to democracy, co-determination, and openness, thus creating unique collaboration between researchers, students and administrative staff.

Six months before the opening of the Department, Peter Naur invited people to an open meeting with the theme “What do we think is essential to the new department that we are creating?”. One of the decisions made was that the students were to evaluate all courses and thus have co-determination on the contents of new courses and how they were taught.

Peter Naur had an innovative approach to teaching. It was important to him that the computer science courses reflected the practice that the graduates would face after completing their study programme. Therefore, the Computer Science programme consisted of extensive group and project work already during the first years. The students were to solve real problems under the supervision of lecturers and older students, rather than studying problems and methods purely from a theoretical perspective.

Importance was also attached to the students acquiring competences in planning and implementing projects. The Department received a lot of enquiries from the corporate sector for help in performing computer science assignments – far more than there was money for. Therefore, the assignments were also offered to students on the ‘Computer Science Internship’ course.

A student as head of department

Peter Naur never really thrived in the role as head of department, and a new department administrator was therefore elected in 1971. For the first and only time in the history of the University of Copenhagen, a student was chosen for this office. This was Flemming Sejergaard Olsen, who acted as department administrator in 1972-73. The Ministry of Education was quick to make sure that the legislation was changed so that this would not happen again.

Even though the Department was established just as the wave of student revolts was rolling across the university world, it never really hit DIKU. Seeing that a student had served as department administrator and as DIKU’s employees generally wished to involve the students, the students were not so receptive to the student revolts.

Explainer: Department administrator

At the time, the head of department was called the "department administrator" because he or she was elected through a democratic process – unlike today where head of department vacancies are posted, and an appointment committee decides who will be appointed to the position.

The change to having a head of department came in 1993, when Jørgen Bansler became Head of Department. Where the department administrator was elected for a 1-year term at a time, the head of department was now employed on a fixed-term contract, typically for five years at a time with the option of an extension.

Unique student culture

Many of the first students at DIKU describe the social life as being very vibrant. Some of the students virtually lived at the Department, where they quickly established a joint food scheme and a canteen association. The students organised hikes and card game tournaments, parties at every opportunity, and many of them got together to create their own computer games.

To this day, the canteen in Universitetsparken 1 remains an important focal point for DIKU students, where they meet across year groups and help each other. The students themselves run the canteen, where you can get a free cup of coffee, and where Christmas lunches, DIY Christmas decorations day and many other activities are held.

There is generally still an active association life among the students. New associations have emerged with each new year group of students, including the hacker group Pwnies, which has reached the finals of DefCon – the unofficial, but famous, computer hacking world championship.

One of Denmark’s oldest student revues

Another key focal point in DIKU’s study environment is the student revue, which started in 1973, and is one of Denmark’s oldest student-run revues. The next revue at Universitetsparken, the Physics Revue, was not launched until in 1989.

A good-natured rivalry quickly arose between the two revues. You can witness this today during the performance of both the DIKU Revue and the Physics Revue. They always start with a loud singing battle based on the computer scientists’ very own battle song, ‘I morgen er verden vor’ (Tomorrow the world is ours).

The DIKU Revue remains one of the absolute highlights of the year among the students. Some of the employees also attend as audience. To begin with, the revue was actually intended as a focal point for the whole Department, for students, lecturers, and administrative staff. The revue thus helped create a sense of unity and traditions at the young Department.

Research during the first years: Naur changes focus

With many students and only a few lecturers, establishing a computer science research environment in Denmark was a major task. The time was first and foremost used for teaching, and several of Peter Naur’s research activities had a scientific-theoretical purpose. He produced a number of articles and textbooks aimed at building up an understanding of the discipline. These works included descriptions of his views on data and the fundamental questions that the discipline had to pose.

Around 1972, Naur also abandoned his interest in the formal work with programming language, and instead began to focus more on how people work with programs. Peter Naur was a pioneer in his view that we cannot design IT systems in advance without including users and their practice. He believed that it was important always to remember that computers are a tool for people.

During the first years of the Department’s existence, research was also conducted into the development of medical measuring systems, especially for measuring brain functions. Denmark’s first female computer scientist, Edda Sveinsdottir, succeeded in constructing a gamma camera with a built-in ‘mini-computer’ in collaboration with her husband, who was already then a world-renowned doctor and brain scientist.

For the first time in history, the camera made it possible to localise brain functions such as speech, vision, movement, hearing and epileptic centres in a living brain. This groundbreaking brain scanning technique, known as tomography, is still being used today to diagnose, for example, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Syndrome.

Teaching during the first years: Underlying universal competences

What did the teaching of computer science consist of in the early years relative to today?

Seen from the outside, the technological development has moved forward at rocket speed over the past 50 years. Some will therefore be surprised to learn that the underlying computer science competencies are virtually the same as 50 years ago.

Writing programs and solving problems with algorithms are universal competencies which have always been part of the teaching. The contents of the courses taught 50 years ago and today, therefore, do not differ significantly. The biggest difference is that we are today able to do much more with our computers.

Over the years, computer software has become faster step by step, and the hardware has become smaller. At the same time, today’s computers can contain much larger volumes of data. The small computers that are today built into our mobile phones are much stronger than the machines used to send the first people to the moon!

At the DIKU of the 1970s, entire floors were used to house the bulky computers in special machine rooms, and the students learned to use tapes and hole cards to store data and input programs. The computers and hole punchers were not DIKU’s sole property, but belonged to RECKU – the Regional Computer Centre at the University of Copenhagen. They were handled by an operator, and you had to apply for permission to become a user to gain access to them.

The possibility of working with large volumes of data today has resulted in the emergence of the sub-discipline of Data Science, which DIKU today offers as an entire Bachelor’s programme (Machine Learning and Data Science). Here, the work especially focuses on learning how to handle, organise and analyse large data volumes.

Another thing that has changed from the early courses taught at the Department and to today is that there is greater focus on the ability to collaborate in large groups. Group work has always been part of DIKU’s study programmes, but as software development projects are conducted on a much larger scale today than 50 years ago, there are greater requirements for being able to work agilely.